A lot of this material goes back some years, but I went through it thoroughly during the Feb ’25 online Emptiness and the Heart Sutra retreat, for AUS/NZ sanghas, and considerably revised it again at Vajraloka in July ‘25, so it is now closer to my current understandings (and is hopefully clearer). It incorporates some of Jayarava’s scholarly insights into the origins of the sutra, and I cannot thank him enough for his brilliant work. However, as Jayarava pointed out, everyone who teaches the Heart Sutra has their own particular take, and I only claim to offer my own takes, not his. This, as the title suggests, is mostly about practice based on the sutra rather than scholarship. Nevertheless, I hope I haven’t misrepresented any of Jayarava’s scholarly conclusions. Some more recent writings on the sutra are towards the end of the document. Sanskrit / Pali diacritics are a bit hit and miss at the moment! I hope it’s helpful overall.

Tejananda, July 2025

Prelude – Origins of the Heart Sutra

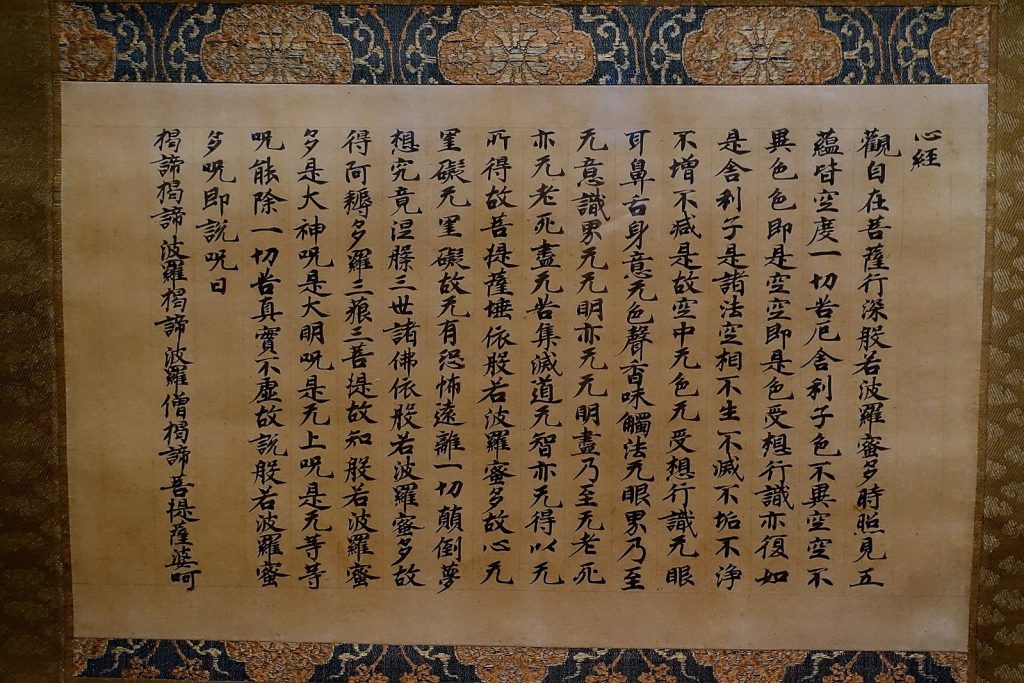

The Heart Sutra isn’t actually a sutra. Its Sanskrit title is simply “Prajñāpāramitā Hridaya”, Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom. The version which we chant in Triratna pujas is based on its original form, which was composed in China. It was compiled from Chinese translations of sections from the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra in 25,000 lines, with some additional material. It possibly originated for use as a dharani, a brief sutra summary, or a protective ‘spell’.

Later, this text having become very popular in China, it found its way to India and was back-translated into Sanskrit, possibly by Xuánzàng. Thereafter, the longer version was created to make it appear like a ‘proper sutra’. As such, it took its place in the body of Prajñāpāramitā sutras and came to be regarded by early western scholars, such as Edward Conze, as an ‘authentic’ Indian Mahayana sutra. However, careful scholarly work by Jan Nattier,[1] uncovered its true origins. Though these findings have been controversial in some quarters, Jayarava’s comprehensive scholarly work has confirmed this beyond reasonable doubt.[2]

This does not in any way undermine its significance and value for us as a Dharma teaching – the main part of it is based on earlier, Indian, Prajñāpāramitā texts. If there’s any concern about ‘authenticity’, bear in mind that from the point of view of many traditional Theravadins, all of the Mahāyāna sutras (and tantras) are apocryphal anyway! Needless to say, this was not Sangharakshita’s view – see ‘The Eternal Legacy’.

1. Finding Heart in the Heart Sutra

The first three words of the Sanskrit version of the sutra are ‘ārya-avalokiteshvaro bodhisattvo’.

Arya – ‘noble’ means one who has realised any of the paths of awakening (stream-entry etc.) It’s significant that Avalokiteshvara, as an ‘arya,’ is visibly ‘empty’ of being male, female (or neither, or both), and this shows up in the iconography: most Indo-Tibetan forms appear male or androgynous, whereas in East Asia, the form (as Guan-Yin) becomes definitively female. This brings out the insight that gender, like everything else, is empty of intrinsic existence (svabhāva).

In Avalokiteshvara’s case, though appearing as a bodhisattva, and so technically not fully-awakened, she/he/they actually embodies all the sensitivity, love and compassion of Prajñāpāramitā itself or herself, i.e. full awakening.

So, it’s Compassion that actually offers the wisdom teachings in the sutra. The Heart Sutra might be a ‘Perfection of Wisdom’ text, but it isn’t the case that Prajñāpāramitā texts are just about wisdom – they are as much about bodhicitta, and bodhicitta is the inseparable union of wisdom and compassion.

Wisdom and compassion are in essence one – we see them as quite distinct qualities, but that isn’t the case. Wisdom and compassion are distinguishable, but they are even closer than two sides of the same coin. Wisdom is compassion, compassion is wisdom. Compassion in this sense is more than a ‘positive emotion’ that we cultivate. This wisdom-compassion is pointing to a quality of awakening itself – something intrinsic to the actual nature of things. When we cultivate heart qualities like metta, we’re approximating on a dualistic level a ‘quality’ of reality itself – reality in the sense of ultimate bodhicitta, ‘absolute’ alaya, dharmakaya, dharmadhatu, the unborn, deathless, etc.

For us, now, compassion is perhaps a metaphor for ‘wisdom of the heart’ and ‘wisdom of the body’ – of embodiment, wholeness, interconnectedness.

It becomes obvious to us at some point that metta is something ‘I’ can no longer cultivate. Self-cultivation can only go so far – that is, only as far as the ‘self’ goes. This means that as long as we see the world from the distorted perspective of self-view, it’s inevitably limited by the belief and perception that boundaries or divisions are real. In particular, the perception of separation into of self and other. All this is mental fabrication.

In the Mahayana a distinction is made between maitri (the Sanskrit word for metta) and maha-maitri. Maitri / metta is the quality of friendliness and love that ‘I’ cultivate, while maha-maitri is maitri conjoined with prajñā – it is unlimited, unconditional and unfabricated, beyond any concept of self or other – in fact, beyond any concept whatever (niṣprapañca).

So ‘I’ can and do cultivate friendliness, kindness, goodwill – and it’s vital that I do so, especially from the point of view of the training in sila, i.e. our interaction with others and ‘the world’ in everyday life. But this is still done by the divided mind-heart which is ignorant, not-knowing (avidyā) of its true nature.

Although ‘heart’ in the title of the sutra refers to the sutra being the ‘essence’ of the Prajñāpāramitā teachings, we could also understand it as referring to the ‘heart of everything’ – the undivided heart or ‘space’ of being (dharmadhātu), which is what Prajñāpāramitā is pointing to. Our heart is broken, or seems to be – separate, isolated, alone – until we realise its true nature.

Compassion (or love) in the fullest sense is ‘empty’ compassion. Empty of any sense of dividedness, separation between a supposed ‘self’ and a supposed ‘other’. This is what ‘undivided heart’ suggests. The undivided heart is the wholeness of ‘this’ as it is – suchness. It’s what we inseparably are and always have been, the sense of being a ‘divided’ heart-mind only arising because we don’t see the truth of śūnyatā, i.e. that the sense of dividedness, separation (which is duhkha) is empty of any real existence.

These limits are purely mind-made. They are not heart-made. If we open to our heart, it may ‘feel’ limited to the extent we believe it’s something ‘here’ (something that ‘I’ experience). If the heart feels contracted, it’s important to acknowledge this – that’s how it’s appearing now. It’s divided, incomplete and that is painful. That is the truth of duhkha manifesting in our experience.

At the same time, this limited sense of ‘heart’ represents a kind of liminal zone, a ‘opening’ to its real, unlimited nature. This is always available and provides a way to contact deeper and more authentic ‘levels’ of heart, or bodhicitta. We can do this by contacting / asking what our heart’s wish or desire is now.

This doesn’t have to be done with any particular expectation of a ‘spiritual’ answer arising. The heart may long for warmth, simple human intimacy, or just good food. Or for whatever is painful or unpleasant in our experience (mental or physical) to go away. There is nothing wrong with this underlying motivation – the desire to be happy is natural. The problem arises from how we usually go about trying to grasp happiness.

But it can go deeper: what’s ‘under’ these wishes? Quite straightforwardly, it’s the wish to be happy, well and free from suffering – i.e. the very wishes we bring to mind explicitly or implicitly when cultivating metta.

And it can go deeper still. What does the heart really long for? If we open to this we may get a sense (however expressed) that it wants qualities such as wholeness, peace, stillness, silence … or simply to be itself, what it truly is.

And we find – if we’re open and sensitive to it – that the heart responds to its own wish – wordlessly, in the language of the heart (though if it were in words it might be something like ‘may it be so’… which also happens to be the meaning of ‘amen’).

The undivided heart of Prajñāpāramitā responds to the wishes of the divided heart, because it is already their fulfilment.

2. Walking the walk

Noble Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva was practising the deep way of the Perfection of Wisdom; He looked down: there were five skandhas and he saw them empty of self-nature.

At the start of the sutra, Avalokiteshvara is deep in prajñāpāramitā – deep in the deep way of the Perfection of Wisdom. More literally, it says he’s ‘practising the practice’ or way, and these words – caryām caramāno – in a non-literal way could well suggest ‘walking the walk’. How do you walk the walk of perfect wisdom? That’s what we’re concerned about here, even though to get at it, we need first to ‘talk the talk’.

How do we get to see and know what actually is? It means knowing directly that our ‘reality’ is the five skandhas and the five skandhas are empty. Empty of what? Empty of any true, solid, stable, independent existence at all. The skandhas are only mental fabrications. The sutra sums up this fabrication as ‘svabhāva’ – ‘own-being’, self-nature, of substantial, inherent or independent existence. This kind of self-nature doesn’t exist and never did exist. There’s no self ‘here’ or ‘out there’ – no actual entity that we can call ‘me’, ‘you’ or ‘that’, whatever. This thoroughgoing emptiness is known as the twofold emptiness of self and phenomena.

We’ll go into this in more practical detail – these few lines are the part of the sutra that we’re actually going to put into practice in this retreat. But it would help first if we could get a bit out of the technical language and express our project more bluntly.

What ‘walking the walk’ means is getting out of living in the abstractions of our mind and into our body and senses. It means, literally, coming to our senses. It’s the mind that’s always ‘talking the talk’ … it has an opinion about everything, can make judgments about another person we’ve never met before in a nano-second, and firmly believes that it’s in charge around here – it’s ‘me’ – the knower, the doer, the thinker, the decider. It’s deeply delusional!

If we’re ‘up in our head’ we need to do what Avalokiteshvara did: ‘look down’ – i.e. bring awareness into the body. Of course, the head is part of the body, but this is a metaphor for coming out of our addiction to thoughts and mental activities and into what are known as the ‘body senses’ – feeling (tactile sensations), seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting. These too are ultimately empty, but first we need see the emptiness of mental identification and cultivate awareness of the body senses in order to enter and explore the unknown territory of our own body and get closer to the direct knowing of emptiness.

3. “Form is emptiness” etc.

In these skandhas, Shariputra: form is emptiness, emptiness itself is form. Emptiness does not exist separately from form; form does not exist separately from emptiness, that which is form is emptiness; that which is emptiness is form. Likewise: feeling, perception, [mental] formations and consciousness.

The earlier Prajñāpāramitā texts that provided the content that was eventually drafted into the Heart Sutra do not say that the skandhas are emptiness, or empty, but that they are illusory:

“It is not the case, … that illusion is different from form. … the illusion is form; form is only an illusion. [and likewise for the other skandhas].” (Jayarava, ref.)

The sense in which the skandhas are illusory is also evoked by the final lines of the Diamond Sutra:

We should see whatever is conditioned as a star, a visual hallucination, a lamp,

An illusion, a dew drop, a bubble, a dream, a lightening flash, a cloud.

This throws light on the practice implications of emptiness in this context. An empty appearance is one that is illusory in that it is not what it seems, i.e. it is empty of being the ‘thing’ (having svabhāva) that it is mentally imputed to be. And all appearances, whatsoever, are empty. So, in practice, we are seeking to see through these illusions at every level, in all five skandhas, because these deluded reifications lead to dukkha.

We can approach this using the perspective of the three lakshanas (trilakṣaṇa), which, as in the Anatta-lakkhana Sutta, point to the five skandhas as empty of stability (permanence), satisfactoriness, essence or substance[3]:

“…is it fitting to regard what is inconstant, stressful, subject to change as: ‘This is mine. This is my self. This is what I am’?”

Here the Buddha skilfully leads the five ascetics to the realisation that there is no ‘self’ which has the characteristics of stability, potential ongoing satisfactoriness and svabhāva in the five skandhas.

Note that in another sutta, he refuses to answer an ascetic who wants to know whether there is, definitively, a self, or no self. This clarifies that anattā is not being presented as a metaphysical or ontological ‘truth’ which has to be believed, or that can be grasped by the thinking mind alone, but rather as a skilful means to see through the underlying causes of suffering.

The skandhas are also empty of any separation of ‘self’ and ‘other’, of ‘things’ and of ‘objects’. No ‘thing’ exists even for a moment. If ‘things’ truly, inherently existed, had svabhāva, this would mean there is no dependent-arising. Pratityasamutpada and śūnyatā are the same truth from different perspectives, each impies the other.

The sense that ‘things exist’ even if ‘they’ are changing is nothing but a mental imputation (belief) unwarranted by direct experience. This can be investigated. There are only appearances in the undivided ‘space’ of phenomena (dharmadhātu)… no really existing division / boundary / border / limit can be found in experience.

For example, notice that the distinction of ‘inner sounds’ and ‘outer sounds’ is purely conceptual. All sounds appear in one undivided ‘space’ (of awareness). The same goes for the other senses constituting rupa, and all the other skandhas – they arise/cease in one undivided, dhatu – space, dimension, sphere.

This not to say that the skandhas don’t exist as experience – they are like illusions because on the basis of just what is seen, heard, sensed and cognised, we ‘make up’ a whole world of ‘things’ which are objects of craving, aversion or ignoring (and all the other afflictive emotions derivative from these basic ones). In other words, we create dukkha.

A note on why it might be that the sutra states, ‘form is emptiness’ rather than ‘form is empty’. There are various ways in which this might be construed. One is that while it’s true that all forms (and all of the other skandhas) are empty of svabhāva, intrinsic existence, and need to be realised as such if one is to become free of (secondary) dukkha, the very nature of the skandhas is not other than the ‘ultimate emptiness’ of prajñāpāramitā itself – to put it another way, relative truth (samsara) is never other than ‘ultimate truth’ (‘nirvana’). This corresponds with the notion of “Maha Śūnyatā” being the realisation of the indissoluble union of samsara and nirvana.

Rupa – Form

Rupa refers to the fabricated experience of tactile, auditory, visual, olfactory and gustatory sensations – feeling, hearing, seeing, smelling and tasting, as ‘forms’. It also includes the experiential aspect of the four great elements: resistance, fluidity, temperature, vibration, etc.

So, rupa doesn’t refer to ‘matter,’ ‘materiality’ or a ‘material world’. The experience of a form is a perception (samjñā) based on a concretisation of a variety of sensations. As such, like all of the skandhas, it is empty of svabhāva, self-nature, inherent existence.

It’s fundamental to appreciate that what we are experiencing now is not an ‘objective’ material world ‘out there’, or ‘in here’. As I once heard Sangharakshita say, “all we perceive is perceptions”. We have no way of experiencing or knowing about a ‘material world’ outside of perception (and perception, too, is empty of svabhāva, as we shall see).

4. “All dharmas are characterised by emptiness…”

In these skandhas, Shariputra, all experiences (dharmah) are characterised by emptiness, which does not arise or cease; is not stained or stainless; is not deficient or complete.

In this context, ‘dharmas’ refers to any kind of experience. The usual translation of ‘phenomena’ can be misleading. Dharmas aren’t ‘things out there’ which supposedly exist independent of experience. In some Abhidharma texts, dharmas are presented as being the most basic ‘building blocks’ of our experiential reality, almost as having a real, ultimate existence. It’s probable that the Prajñāpāramitā sutras are countering this literal kind of understanding.

From the practice point of view, dharmas can be approached as experience in the most ‘minimal’ sense – sensations that are vibrational, energetic and gone almost before they are cognised.

These are quite within our ordinary experience – we can attune to the subtle, very fast ‘tinglings’ of the energy body, of ‘scintillations’ or ‘visual snow’ in sight (try sky gazing), and of the ‘unstruck sound’ or ‘nada sound’ in hearing. We can get any of these ‘in view’ and notice their characteristics: they arise and pass so rapidly that they can’t be found or fixed as substantial ‘things’ or ‘entities’ that really arise and really cease. Awareness of them can be an entry point into ‘just what is seen, heard, sensed, cognised’ and also into a sense of the undivided nature of the sense fields.

Earlier translations of the sutra tend to view “not arise or cease; not stained or stainless; not deficient or complete” as referring to ‘dharmas’, but Jayarava’s work shows that it seems far more likely that these qualities refer to ‘emptiness’. This actually makes far more sense, and I’ve modified my translation above in the light of this. His own translation of this section goes: “Here, Śāriputra, all experiences are characterised by emptiness: which doesn’t arise or cease; isn’t pure or impure; isn’t complete or deficient.” Emptiness itself is ’empty’ of these or any other dualities[4].

Vedanā – Feeling

‘Feeling’ arises in dependence on ‘contact’ or bare sensation. It could be said that whatever sense door is subject to contact has a certain degree of vibrational intensity which is instantaneously grasped by the mind (at an unconscious level) as tending towards pleasure, pain or neither, i.e. ‘neutral’ vedanā.

All sensations (of all six sense fields) have vedanā, whether pleasant, neutral or unpleasant. However, vedanā is not a ‘fixed quality’. Depending on other factors, what is essentially an identical quality of ‘bare sensation’ could be construed as either pleasant or neutral, painful or neutral. It’s even possible to construe painful vedanā as pleasant.

A mind which is afflicted by avidyā, delusion or ignorance, and also lacking any mindful awareness, will tend to react to vedanās, especially intense ones, with craving, aversion, ignoring or another afflictive emotion (kleśa). However, with practice, vedanās can be turned towards without ‘crossing the gap’ into tṛṣṇā (‘thirst’, craving, which also can manifest as aversion or ignoring).

Inquiring into self in vedanā: If strong pleasant or unpleasant sensations arise, the self-view tends to arise immediately, with an impulse of “I want” or “I don’t want”. If it’s neutral vedanā, it’s more like “I’m not interested”, and it may not even be noticed. Spend some time noticing vedanās as ‘just feeling’, dwelling in the ‘gap’ and not reacting into craving or aversion, let alone acting on it. This can be a very uncomfortable ‘place’ to be.

Notice the sense of “I”, and notice what happens to the emotion if you resolutely stay in the gap, experiencing the sensations, but not reacting ‘over’ the gap (can you find anything ‘making’ or ‘forcing’ you go over the gap, inevitably)? As you stay with the sensations/vedanā, plus the ‘selfing’ you should notice it reach a peak and then subside, along with the selfing. Where is the “I” now?

5. “In emptiness form does not exist”

Therefore, Shariputra, in emptiness, form does not exist, nor feeling, nor perception, nor volition, nor consciousness. There is no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind. No form, sound, smell, taste, touchable, or mental object. No eye-element, up to no mind-consciousness element. No ignorance, no destruction of ignorance, up to no old age-and-death, no destruction of old age-and-death. No suffering, cause, cessation, path. No insight-knowledge. No attainment.

The sutra is a pointer to how we practice, what unfolds in the course of practice. First we see, directly, that what we are, the constituents of our (relative) being, the five skandhas, is ‘empty’ of self-nature, svabhāva, of any truly-existing ‘self’ or substance (and implicitly, empty of permanence and satisfactoriness). Then we see more expansively: all dharmas, all kinds of experience, whether conceived as ‘internal’ or ‘external’, is empty of any intrinsic nature. Illusory. We see through ‘other’ as well as ‘self’. But there may be a sticking point – remaining fixated on, attached to, the relative expressions of the dharma itself.

So, Avalokiteshvara now points out that in emptiness, ‘where’ he has just been dwelling (aka prajñāpāramitā), the five skandhas are not just empty, they ‘do not exist’ – ‘In emptiness there is no form (feeling, etc).’ And also, no eighteen dhatus, no twenty-four nidanas, no four noble truths, no jñāna or insight-knowledge, and no attainment. It’s not that things exist but are empty (of svabhāva), they do not exist at all.

A little bit of etymology may be helpful here. For a ‘thing’ to exist, it must manifest or appear. ‘Exist’ comes from the Latin ex(s)istere / exsistō, meaning to step out, to emerge, to appear, to stand forth. Later, the Latin meaning shifted to ‘having actual being’ and by the time it became incorporated into English, in the mid-17th century, it had the meaning of ‘having objective reality or being’ (courtesy of ChatGPT). Interesting, as a side note, that English speakers had no way of talking about ‘existence’, as such, until the 17th century.

So, in Buddhist terms, there are appearances which arise in dependence on the conjunction of sense organ, object and consciousness and are therefore empty of any intrinsic nature, svabhāva. This is true of the five skandhas and all dharmas, but it doesn’t quite get to the nub of the matter.

As mentioned above, dwelling in emptiness, as Avalokiteshvara was at the beginning of the sutra, equals dwelling in deep prajñāpāramitā – the unformed, unfabricated, unborn dharmakāya. To dwell fully in prajñāpāramitā is to go beyond all experiencing, nothing comes into ‘existence’. There is no experience of self or of the world of the five skandhas, the entire conditioned realm. There is just the dhātu (dimension), beyond space and time, of non-delusion. This is vidyā, as distinct from avidyā, (in Tibetan, rigpa).

This is known as saññnavedityanirodha in earlier Buddhism, which means the accomplishment of complete cessation of all experience. Arguably this is a ‘temporary’ nibbana. On emerging from this deep prajñāpāramitā (without any ‘me’ there to be immersed) it is clear beyond any doubt that prajñāpāramitā – or vidyā, or dharmakāya – is ‘reality’ and that self and world is an illusory ‘projection’ from it.

At another level this section can be seen as emptiness deconstructing the Dharma-as-teaching itself. Sangharakshita, in his commentary on the sutra (see Wisdom Beyond Words), says it ‘eliminates religion considered as an end in itself’.

In other words, it’s making the same point as the parable of Dharma as raft – it’s what gets you there – to the ‘other shore’. To the extent that we hang on to or reify Dharma practice, it ceases to be Dharma practice. If we rely literalistically and rigidly on any approach to practice, we’ll find we reach a ‘glass ceiling’ and can’t go any further. The Buddha didn’t teach in this way, and neither did any of his awakened successors – the dharma brings us ‘back’ to life as it really is, it brings us to what we really are. It’s living truth, and if we were to have sutras on the shrine only as objects of reverence, instead of plunging into them for what is helpful and alive in opening us up to how things really are, we wouldn’t get very far.

So in effect this section is telling us to see the moon, not fixate on the pointing finger. The finger points – it would also be literalistic to say we should ignore Dharma teachings, but never forget they are always concept, not reality – provisional truth, not actual truth.

It really means that we need to make the Dharma our own. Forms and teachings are important, indeed indispensable, but they really demand that we experiment, find our own way with them – find the way to deeper genuine understanding in our experience, not a simulacrum of someone else’s, however ‘enlightened’ they may appear to have been.

Samjñā / saññā

The constituents of the word mean something like ‘together’ and ‘knowing.’ The usual translation is ‘perception’, but from early canonical sources, it’s clear that ‘recognition’ is a better rendering. That is, regarding it as the mental process whereby arisings to the senses are ‘re-cognised’ as such-and-such a thing: ‘yellow’ is recognised as such before any labelling as ‘yellow’. If we were suddenly able to see a completely new colour, it would be ‘cognised’ as colour but not ‘re-cognised’ (sam-jna), mentally identified, as a particular, known colour.

Similarly, we can have the experience of an ordinary sense-arising that’s cognised but not recognised … samjna can be noticed as ‘trying’ to recognise or place what it is.

Allow ‘noticing’ without labelling – we don’t normally, grossly, label everything that’s perceived anyway. When labelling happens, notice how that by abstracting, it ‘obscures’ the clear-seeing (hearing, etc.) of the sense arising. Open to ‘pure perception’ where the mental associations, other than immediate recognition, are absent.

With pure perception, we’re not perceiving a ‘thing’ or ‘object’ – we generally think “I’m perceiving”, but equally, you could say there’s just perception of what is there, in the sense fields, without projecting any-‘thing’ onto it. When it’s seen in this way, there’s no seer or seen separate from each other – there’s just ‘this’, as it is.

6. “Non-attainmentness”

Therefore, Shariputra, because of their non-attainmentness, relying on prajñāpāramitā, Bodhisattvas dwell with the citta uncovered (acittavarana); because there are no ‘citta-coverings’, they are fearless. Transcending distorted (/inverted) views, complete nirvana is attained.

The previous section ends ‘(In emptiness there is) no attainment.

What do we attain by spiritual practice? Absolutely nothing! This counters the conventional view, which is quite likely also the initial view of people taking up Buddhist practice, that “I am going to attain” awakening or enlightenment. In fact, a lot of Buddhist language could support this view, e.g. “I shall attain enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings” could reinforce such a view, if taken literally. When “I” is used in Buddhist contexts, it always needs to be taken with a pinch of salt – i.e. seen as a necessary linguistic convention, not an actual ‘thing’.

As long as we regard awakening in in the light of ‘attainment’, we’ll always be creating and sustaining the sense of separation from it.

Recollect that emptiness is emptiness of svabhāva, of there being a ‘true essence’ to any ‘thing’ that is conditioned. Which also implies that there are no ‘actual things’. Once we see and know directly that the ‘self’ or substantial, independent ‘me’ we believe ourselves to be never existed in the first place, how can what is now known as a mental construct possibly be supposed to ‘attain’ awakening?

An aspect of the awakening process is ‘waking up’ to the complete non-existence of separate self-other. That means waking up to an undivided wholeness which embraces and transcends all dualities.

This section of the sutra expands on this – anybody who’s woken up has by definition depended on prajñāpāramitā – by whatever name.

Here, ‘prajñāpāramitā’ points to undivided wholeness not only beyond the ‘self-other’ dichotomy but beyond the dichotomy of relative and ultimate, samsara and nirvana. This is equivalent to Sangharakshita’s third ‘level’ of śūnyatā, ‘maha-śūnyatā’. For this to be realised fully, the ultimately non-existent mental ‘veils’ (divisions, limits, obscurations) of klesha and jneya would have to have been seen through and have dropped away.

These ‘veils’ are really, ultimately, nothing but emotionally charged views and beliefs – our reality has never been other than undivided and whole. At the same time, this doesn’t mean undifferentiated – there are endless differentiations that can be made, starting with ‘saṃsāra and nirvana’, but in reality, everything arises non-separately in undivided wholeness.

Knowing this (knowing beyond conceptual mind-knowing, of course), fear disappears – i.e. all need to protect ‘my self’ drops away, when we see how it actually is. Things are seen ‘the right way up’ and delusion together with craving-aversion drop away – which is nirvana, i.e. the ‘blowing out’ of the flames of delusion, craving and aversion.

Although in the full realisation of this is the province of buddhas, bodhisattvas and arahants, an ‘opening-up’ to undivided wholeness could emerge ‘here-now’ any time.

Saṃskāra

As a skandha, ‘saṃskāra’ refers to a conditioning mental factor, skilful, unskilful or neutral, which has a karmic effect, in other words a result in terms of conditioning more or less future suffering. So, collectively saṃskāras are mental events, mental-emotional ‘formations’ and habits – thoughts, images, emotions and the resulting actions.

Saṃskāras are broadly parallel to cittas in the Satipatthana Sutta. The ones to watch for are those that embody ignorance-craving-aversion and other derivative afflictive emotional habits. Samskaras are habitual ways of thinking, relating or understanding. They are the ‘default mode’ – in Sangharakshita’s terms, ‘reactive’ as distinct from ‘creative’. ‘Creative’ suggests a quality of action that arises from emptiness, not-self, wholeness.

Saṃskāras are also empty of self. The self-view is created and sustained by saṃskāras, our thoughts, by the way we believe in the reality of what we think and imagine. This is sometimes referred to as the ‘narrative self’ – our ‘me’ stories in which we have become unconsciously enwrapped. Even in well-adjusted people, without any insight (prajñā), this thought-identification is delusory and often painful.

The self-view collapses when we see through this mental identification – the apparent ‘substantiality’ of our mental ‘forming’ as “me”. This can be accomplished, among other approaches, by experientially contemplating the three characteristics, by focusing on ‘selfing’ thoughts until they dissolve into the ‘space’ of consciousness in which they arise, or by ‘looking’ for the self-entity in every area of our being – body, thoughts, decisions, sense experiences, etc, to see whether a separate “me” entity can be found.

As Sangharakshita observed, the self-view is mainly cognitive (though with a good deal of emotional holding-on). Seeing its empty nature directly and not just conceptually is a very feasible initial opening to prajñā. Its dropping away is by no means the end of the path of wisdom – but it is a very significant beginning.

7. Prajñāpāramitā

All Buddhas of the three times are fully awakened to the utmost, perfect awakening by relying on prajñāpāramitā.

Full awakening is realising prajñāpāramitā, so by definition, all who are awakened, i.e. Buddhas (‘awakened ones’), are awakened because of prajñāpāramitā. That’s why Prajñāpāramitā is referred to as the ‘mother of all the Buddhas’. Prajñāpāramitā is also the ‘Womb’ of the Tathagatas (tathagatagarbha), or the ‘Primal Void’ of dharmakāya beyond all dualities – Unfabricated, Unborn.

Prajñāpāramitā is synonymous with jñāna in the sense of ‘undivided awareness’ (i.e. jñāna distinct from vijñāna as separative consciousness or ‘divided awareness’).

It’s also related to the principle of ‘spiritual rebirth’ in Sangharakshita’s system of meditation, with emptiness representing ‘spiritual death’. We practice shila, samadhi, prajña – skill in action and cultivating mental calm together with penetrating insight. In our system of practice this takes the form of integration, positive emotion, spiritual death and spiritual rebirth. The non-practice’ of just sitting, simply being, or ‘spiritual receptivity’ is integral to this.

Spiritual ‘death’, as I understand it, is initially aimed at seeing through self-view, and involves whatever practice is done to effect that seeing-through. Seeing directly that one’s self-view is nothing but a view, a belief, is where the path of insight really begins to bite – it’s the moment of fundamental, experiential entry into the Dharma.

There may be openings to direct knowing of the undividedness of ‘the perceptual situation’ when the self-view collapses, but this is unlikely to open up in a stable way at first. Any genuine shift in perception, as with the self-view, needs to be consolidated by ‘recognising’ again and again. Then more practice and investigation will be needed to fully see through the self-other or subject-object dichotomy completely.

In addition, even with a genuine arising of insight or wisdom, there’s still a huge amount of ‘habit-energy’ (samskara) at work, including unskilful habits, beliefs and all our psychological conditioning, trauma and so on. So, it sometimes can seem that we haven’t actually changed and we’ve ‘lost it’. The more ‘we’ try to get it back, e.g. using the old ways of practising, the more inaccessible it can seem. If this occurs, a different paradigm is needed. One such paradigm is non-practice. Rather than trying to ‘get’ further, it means being utterly simple, open, receptive to ‘just what is’.

But this is not something that only comes into play after prajñāpāramitā or non-separation is known directly – as just sitting or ‘spiritual receptivity’ it’s part of our practice from the beginning – just being, relaxing, opening, into whatever is, just as it is.

This openness is where prajñāpāramitā can always potentially ‘reveal itself’, because it’s letting-go of self-will (which is only another mental construct), letting go of ‘me doing this practice’. Once prajñāpāramitā is ‘known directly’, it becomes the fundamental non-practice, which embodies all the principles of the apparent path that we’ve apparently trodden…

This is not to say that we should drop other cultivation and insight practices. If there has only been a glimpse of prajñāpāramitā, they are still needed for going deeper. But when the ‘view’ of prajñāpāramitā or non-separation is well established, practice is done from the ‘view’ or perspective of of non-separation, wholeness, being, suchness.

Vijñāna

As one of the skandhas, vijñāna is usually translated as ‘consciousness’, or ‘sense-consciousnesses’. The word vijñāna consists of ‘jñāna’, knowing and ‘vi-‘ which implies ‘apart, distinct, divided, differentiating’. In other words, a vijñāna is a consciousness which perceives (created) a subject – object duality. It appears to be ‘my’ consciousness of ‘that’ which is separate from me.

Vijñāna, then, is a mental process and each sense arising – right down to the finest ‘scintillation’ or ‘tingle’ – is a new and unique (divided) consciousness. As this depends on conditions, vijñāna too is empty of svabhāva and, creating as it does an illusory sense of self / separation, it is a conditioning factor that sustains delusion.

Vijñāna is to be distinguished from undivided awareness (or consciousness) i.e. jñāna as distinct from vi-jñāna. Jñāna and prajñā are undivided knowing which doesn’t condition a deluded ‘perceptual situation’. So, vijñāna necessarily involves avidyā, ‘not-knowing (how things really are)’. A mind clouded by avidyā perceives ‘objects’ or ‘things’ as if they have a true, substantial existence ‘from their own side’.

The Heart Sutra offers the perspective that there are no separate or independent ‘subjects’ or ‘objects’. The undeluded nature of awareness or consciousness is undivided knowing.

How do the skandhas condition deluded knowing and being? Here’s one way of looking at it. Essentially, at the moment of any sense arising (i.e. contact) vijñāna operates as an instantaneous, unconscious, mental act of dividing the experience into two, knower and known. At this point, the just-created ‘object’ aspect is recognised (saṃjñā) as a ‘thing’ or form (rupa) which is separate from ‘me’ the subject. Subject and object are mutually dependent and arise simultaneously.

Right away, a feeling-tone arises towards this ‘thing’ (vedanā), which increases the sense of substantiality, we think and proliferate about it (saṃskāra) and this reinforces the perception of what appears to be a full-blown, substantial, really-existing dualistic object (rupa again). All this happens in a millisecond, and until it’s seen through by prajñā, it happens continually. We’re off on a wrong footing from the start because in vi-jñana there is the kernel of separation into subject-object already, and by the time any construct of self/world appears, it seems substantial and ‘real’.

So, moment by moment, a deluded view of ‘reality’ is occurring. This is deep and habitual, but it can be seen happening and seen through – if it wasn’t, we couldn’t wake up from it. We have to kind of work backwards on this – see directly that form (self/world) is empty of any really-existing self and therefore empty of other too, then the same with feeling, recognition, formations and consciousness.

Then the whole mental construct drops away and we ‘rest’ in prajñāpāramitā – jñāna, pure presence, unborn Buddha mind.

8. The Power of Gone

Therefore, one should know prajñāpāramitā to be the great dhāraṇī, the dhāraṇī of great knowledge, the unsurpassed dhāraṇī, the unequalled dhāraṇī, the dhāraṇī that calms all suffering; one should know it to be real because it is not false. In prajñāpāramitā, the dhāraṇī is recited thus: gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha.

The sutra almost seems to be bigging this up as the ‘best’ dhāraṇī. In the Mahayana, a dhāraṇī is a mantra-like condensed expression of a teaching and can hold the essence of entire sutras or paths. But here, the dhāraṇī is a place-holder for prajñāpāramitā itself. From the viewpoint of avidyā, delusion or ignorance, the Heart Sutra dhāraṇī is pointing us ‘back’ to our true nature, bodhi, the unfabricated, unborn, ‘natural state’.

This is why prajñāpāramitā is said to be the pacification of all duhkha. An integral aspect of prajñāpāramitā is jñāna, non-separative knowing, while (secondary) duhkha only arises from the perception of separation, condidioned by vijñāna. By contrast, in prajñāpāramitā everything is ‘perfect just as it is’.

Many dharanis consist mainly of (apparently) ‘meaningless’ syllables. However, the construction of the Heart Sutra dharani makes it possible to correlate it with various paths consisting of ‘fours’ and ‘fives’. In terms of the four śūnyatās which Sangharakshita derived from prajñāpāramitā sutras, the first ‘gate’ is emptiness of the conditioned, the second is emptiness of the unconditioned, ‘paragate’ is maha-śūnyatā, the integration or union of relative and ultimate truth and parasamgate the emptiness of emptiness – the path of no-more-learning, bodhi, full awakening.

Another way of looking at the dhāraṇī is that it’s just hammering at: gone, gone, gone! What’s ‘gone’? THIS is gone – whatever we think is ‘here’, is actually gone. This moment is gone – in fact, never actually existed. Seeing and knowing this directly is entry into complete openness. ‘Gone beyond’ is the spontaneously-arisen nature of what-this-is, and ‘gone altogether beyond’ is being awake in its utter simplicity

There are many ways of construing this. In the end, the dhāraṇī doesn’t have to be construed or interpreted, we go beyond words and concepts – just ‘hear’ and know its truth – prajñāpāramitā is this right here and now.

Appendix 1

Inquiry into ‘self’ (svabhāva) in the skandhas

This is intended to give you some perspectives on how you could contemplate / inquire into the belief that an independent, single, permanent, potentially satisfactory and substantial ‘self’ resides or somehow exists in or in relation to the skandhas. Feel free to experiment and use parts of this and not others – whatever you engage with and find effective.

- Set up posture with a sense of ‘grounding’ – then do whatever you find helpful to get into ‘basic presence’ and open to unconditional love / compassion.

- Simply be open, directly aware of all the varieties of sensation present in experience now.

- Become experientially aware of the skandha you are looking into (as outlined below), or an aspect of it. Just experience it as it is for some time.

- Look / feel directly with the discerning quality of awareness rather than thinking: Is there a sense of ‘self’, ‘me’ ‘I’ or ‘mine’ in relation to the skandha you’re attending to? What actual experiences are you attributing ‘self’ to or do you feel your ‘self’ to be?

With each skandha, I suggest using a fairly simple, experiential approach:

- Forms as the experiences of the five ‘body senses. These are feelings of body sensation (somatic ‘aliveness’), plus seeing, hearing, smelling and tasting. Notice which of these you grasp onto most strongly as ‘me’, ‘myself’, ‘what I am’ at the time, and inquire into that.

- Feeling-evaluation – Be aware not only of pleasant, neutral and unpleasant feelings but also the incipient “like”, “don’t like” or “not bothered” evaluation that’s part of it.

- Recognition-grasping – With whatever sense arising is happening now, notice the immediate direct recognition of each sense experience, with our without overt labelling. Also notice any impulse towards ‘want’ or ‘don’t want’ along with this recognition.

- Formation-proliferation – Notice any compulsive, repetitive mental proliferation (prapanca) around objects of grasping or repulsing. Finding the ‘sweet spot’ to contemplate this is something of an art, given the nature of prapanca. Try being aware of a relatively mild expression of craving or aversion, something that doesn’t draw you in completely.

- Consciousness – This is our divided or dualistic consciousness of some-thing (vi-jñāna). Notice how, with any sense arising, there is a tacit assumption or feeling that there is a ‘me here’ having the experience of ‘that there’.

- You can use any of the following questions to set off your search for the ‘self’ in each skandha. Be sure you are aware of direct experience of the skandha as it appears to you now – this is what you are looking (inquiring) into. It may well be enough to just explore one of these questions per session, with one of the skandhas. I’ll use the example of visual form here:

- Is it that visual form itself is “my-self”, what or who I essentially am? Where in experience of visual form is that “me” to be found? What does it look like, what does it actually do in terms of enabling that skandha to function or appear?

- Am I the possessor or experiencer of visual form, existing independently of it? If so, where is that separate me to be found? What does it look like, how does it enable the experiencing of the skandha?

- Is visual form part or an aspect of my-self? (In which case, all five together may seem to be the self – but if they individually aren’t self, how could all together be?)

- Or is my-self an aspect of visual form? If that seems to be the case, again where is it, what does it look like, how does it function as an aspect of the skandha?

- Let go of any reflecting, cultivating or directed effort and just sit ‘as you are’.

How does the Heart Sutra point us to awakening?

Form is emptiness / form is illusory is the bit of the Heart Sutra which people remember, and it’s an excellent pointer to awakening, that is, waking up to the non-conceptualised, ineffable ‘this’ which is our true nature.

‘Form’ encompasses all five skandhas, which are the conceptualised world, the world literally made up by the mind, from Nothing[16].

If we try to get our head round this – and we do of course – we just end up mentally spinning round and round endlessly. It’s not a pointer to thinking more, studying more or maybe learning Sanskrit so that we can understand the sutra better (as I once did!) – it’s a pointer to the actual condition of things (no-things) – the awakened ‘non-state’ which is and has always been ‘here’. In this context it’s labelled ‘prajñāpāramitā’.

Buddhist words and concepts don’t always help, because people fixate them with a kind of ‘Holy Dharma Meaning’ – this is the 3rd fetter at play – and even worship the printed texts of the Prajñāpāramitā[17]. There’s nothing wrong with this in itself, as a devotional practice, but it needs to be as well as, rather than instead of, honouring their true purpose: they point us directly to how we may wake up.

It seems likely to me that the Prajñāpāramitā began as an attempt to get out of this literalistic kind of tendency. ‘Form is emptiness’ means, in effect, ‘don’t conceptualise forms, look at what is really here’- what is the actual experience of what we take to be ‘forms’? Emptiness is the completely undefinable, indeterminate openness that what we regard as‘forms’ actually are. Forms as such don’t come into existence (and, of course, the same applies to the other skandhas).

How to put this into practice?

Look at, feel – be aware of – your own experience right now. There’s probably a stream of thinking, commentary and mental imaging going on. That’s fine – just don’t pay any heed to whatever it’s ‘saying’.

Settle into the experiencing. Notice that the experiencing is always changing, always fresh, and happening of itself. Notice that there is just experiencing – there is no ‘experiencer’. And notice (with ‘awaring’, not thinking) that there is no experience of past or future – there’s just this, whatever ‘this’ may be – a sound, a sight, a thought, a body sensation.

Is there a sense of aliveness, awareness, presence or a simple being-ness, always here? Notice that totally inseparable and intimate with this, at no distance, stuff is happening – seeing, hearing, thinking, imagining and so on. But also notice that the stuff that is happening isn’t happening in time, at all. There is no experiential continuity, experience has no duration and no ‘things’ (including ‘me’) are being constructed, unless the conceptual mind comes in and creates a sense of time and space and ‘things’ – especially the separate ‘me’ thing – persisting in time and space. There’s just this pure, knowing, timeless presence inseparable from these incredibly ephemeral and spontaneously arising sense impressions.

Experientially, there is no persistence of anything, and ‘this’ can’t be labelled or described, which is why, as well as prajñāpāramitā, it’s sometimes referred to as ‘suchness’, as in ‘is is such as it is and that’s all you can say’!

In this way, opening to openness – without any attempt to ‘do’ it – could suddenly resolve into the immediate awake presence which is always here but usually well covered-up by mental proliferation. There is just ‘this’, empty of any fixation – it’s not ‘forms’, not ‘feelings’, not ‘recognitions’, not ‘mental stuff’, not ‘me conscious of something’. In fact, there is no sense of ‘me’, or ‘other’ at all. There is just a relaxed, non-referential complete openness in which, in Milarepa’s words, ‘just about anything can happen’[18].

Awakening (bodhi) is suggestive of a process, not a state that is finally ‘attained’. The end of the process is the end of awakening. Awakening is gone – ‘awake ’ / ‘not awake’, along with all other dualities, simply no longer applies.

[1] https://jayarava.blogspot.com/2007/09/heart-stra-indian-or-chinese.html

[2] Jayarava has done a huge amount of scholarly work on the Heart Sutra and Prajñāpāramitā in general, so if you have an appetite for scholarly approaches, check out https://jayarava.blogspot.com/p/prajñāpāramitā.html

[3] Empty of the first three viparyasa, or ‘upside down views’.

[4] Note that this revision corresponds with the original form of our chanting version “All things are the primal void [emptiness], which is not born or destroyed…”. The revised version makes it seem that ‘things’ are the object, not ‘emptiness’: “All things are by nature void, they are not born or destroyed…

[5] Prajñāpāramitā is complete and total openness right here-now, empty of any mind-made division, separation, reification or fixation. It is devoid of any opposites whatever. The indivisible timeless ‘moment’ is always here, inseparable from the ungraspable ‘this’ arising here-now, which is totally embraced-released, loved, let go (by no-one) and lasts no time at all. Knowing-known are one. Knowing is relaxed, resting back, peaceful and unconcerned. There is no evaluation or investment for or against. The soma is already of this nature. What is known is gone already, spontaneously and timelessly self-arisen self-liberated. This process can take some time to open up, but is always timeless.

[6] Skandhas

[7] I.e.’secondary’duhkha.

[8] Openness – śūnyatā. “The open dimension of being”. Dwelling as openness is non-determinate unmediated awareness without even the slightest mental projection or imputation; it is what it is – a completely unimpeded natural flow.

[9] Vi-jñāna. The five skandhas are simply conceptual labels we unknowingly put onto direct unmediated (or unfiltered) experience

[10] As in the Bahiya Sutta – ‘In seeing just seeing, in hearing just hearing’ etc.

[11] All this was just concept

[12] ‘Bodhisattva’, ‘awakening being’– that means us

[13] With the conceptual mind

[14] But not necessarily all at once or without being ‘helped on their way’ with more inquiry.

[15] The rendering of the last couple of lines of the sutra and the dharani are intended to undermine any kind of ‘spiritual solemnity’ – the sutra, and especially the dharani, are expressions of the joy of liberation.

[16] I’ve capitalised Nothing to indicate that it’s not ‘just nothing at all’ – a non-thing, it’s the ineffable, ungraspable nature of ‘this’ as it is – the Unborn, the Deathless, the Unconditioned, etc.

[17] The rendering of the last couple of lines of the sutra and the dharani are intended to undermine the kind of ‘spiritual solemnity’, a kind of ‘Buddhist Puritanism’ – the sutra, and especially the dharani, are expressions of the joy of liberation.

[18] Anything at all, in fact. As Milarepa sang:

I eat the food of empty space,

I meditate without distraction,

I have different experiences,

Just about anything can happen!

E ma, the phenomena

Of the three realms of samsara,

While not existing, they appear,

How incredibly amazing!